Section I: The Skyline of Ambition

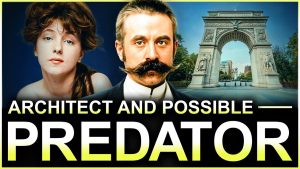

New York in the Gilded Age was a stage, and Stanford White stood center stage, a tall, red-haired figure whose presence could bend light and influence. The city’s rising towers, the newly minted marble, the clubs that hummed with men who could buy a continent’s worth of time, all bore his fingerprint. White did not merely design buildings; he choreographed entrances, orchestrated first impressions, and turned urban space into a theater where wealth, taste, and power converged. His entrance into the world of McKim, Mead & White was not a timid ascent but a decisive assertion: a junior partner who carried himself with the confidence of a founder, a man who could downplay his youth by the audacity of his vision. The studio and the drafting room became his proving ground, a place where he learned to translate a patron’s dream into stone, glass, and spaces that felt inevitable, as if the city itself had chosen these forms to express an era’s longing. It was in this crucible of ambition that White’s appetite for scale sharpened. Trinity Church in Boston, his earliest grand tableau, taught him an essential law of architecture: magnitude is not merely measurement but mood. The nave’s shadows and the light that caressed the chancel mattered as much as the height of the spire. If the era demanded monuments that could outshine a moonlit night, White’s hand could render towers that seemed to breathe with the city’s breath, spaces that demanded reverence and, equally, ownership. And ownership was the currency of the Gilded Age: the ability to decide what the urban horizon would look like, what public life would feel like, and who would walk through the doors of the city’s most consequential buildings. The Washington Square Arch, the Madison Square Garden that would replace its more modest predecessor, and the exclusive precincts of the Metropolitan Club were not accidents of taste; they were deliberate acts of design that defined a social order. The arch framed a city that wanted to tell its own story in a single breath, and White, with the elegance of a conductor, ensured that every stone, every silhouette, every carefully selected ornament would sing in harmony with a narrative of wealth paired with cosmopolitan refinement. Yet even as his name became synonymous with architectural daring, a more troubling current moved beneath the surface. The Gilded Age was a period when networks of influence—clubs, patronage, family legacies—could shelter ventures, arguments, or reputations under a velvet curtain. White’s ascent occurred within this climate, where an eye for beauty and an appetite for risk could be as valuable as a ledger of commissions. The city’s skyline was not merely a backdrop but a canvas upon which the era could project its most confident self-image: that civilization could be sculpted through taste, discipline, and a certain, almost theatrical, command of social capital. White’s early triumphs—his role in shaping the firm’s ethos of “total design,” the capacity to curate every detail from façade to interiors to furniture—were not just professional achievements; they were acts of cultural persuasion. The idea that architecture could be art and social life at once—this was White’s thesis, and the proofs were in the public spaces that hosted the city’s brightest souls, its wealth, and its most daring ambitions. The architecture of the period was a language, and White spoke it fluently: he could translate the rhetoric of antiquity into modern infrastructure; he could claim the aura of classical permanence while negotiating the practicalities of commission, client, and market. The city’s memory would eventually remember his name as a symbol of big ideas realized in stone, a symbol of a era that believed that grandeur could be democratized through taste, institutions, and the controlled spectacle of architectural events. But this first act would also seed the tensions that would later define his legacy: a collision between private appetite and public achievement, between the public trust placed in a man who could shape civic space and the private ones that no archive easily reveals. The drama of White’s rise was, in essence, a drama of the city itself: a metropolis learning to look upon its own reflection in marble and glass, to believe that architecture is not just a craft but a moral project, a quest to build a world that would outlive its inhabitants and outshine its own failures. In the pages of history, White’s fingerprints appear as the punctuation marks of a sentence that declared: we will be seen, we will be remembered, and we will redefine what it means to be modern. The question that lingers is not merely what he built, but how a culture measured the price of such beauty, and who paid it when the lights went down and the urban roar hushed into the dark hours of the night.

Section II: The Constellation of Influence

If we pry open the social lattice of the late nineteenth century, we find White not just as a designer but as a node in a network that linked money, taste, theater, and politics. The clubs—Metropolitan, Union, and a constellation of others—were not mere leisure spaces; they functioned as discreet headquarters for knowledge, leverage, and matchmaking. White moved within these rooms with the ease of a conductor collecting the orchestra’s cues: a glance here, a recommendation there, a whispered word that could tilt a commission into the light. The portraits of the era show men wearing velvet and ambition, women navigating threads of social expectation while seeking opportunities that could lift their names into the pages of society, the way a building’s cornice lifts its façade toward the sky. White’s social calendar, dense with appearances, projects, and dinners, was a choreography of influence. He did not simply win clients; he curated environments that reinforced a particular worldview: that beauty is a currency, that public admiration can be monetized, and that the line between artistic genius and social power is thin enough to walk with grace, if one has the nerve and the means. The partnership with McKim and Mead—founded on shared aesthetics but complicated by competitive ambition—formed the backbone of a practice that could absorb talent, orchestrate partnerships, and deliver a portfolio that read like a social register: Vanderbilt, Morgans, Whitneys, Pulitzers, and Morgans again, a roster that could turn a dream project into a city’s landmark. This network did not merely supply commissions; it created an ecosystem in which ideas about modern life—about public space, about private luxury, about the theater of daily existence—could be tested, refined, and serialized into urban form. The Metropolitan Club, in particular, stands as a monument to the idea that elite spaces could be instruments of culture as well as power. Its rooms were stages for conversations that would shape policies, philanthropy, and the very culture of patronage. The club’s reputation, as reported by prominent outlets of the era, as one of the wealthiest and most exclusive clubs, is a reminder that White’s talents extended beyond the architectural into the social engineering required to maintain such an institution’s aura. To understand White fully is to understand the architecture as a social technology: a way to bind clients to a shared language of taste, to translate private aspiration into public monuments, and to embed a personal brand within the city’s moral ledger. The grading of success in this world depended not only on the beauty of the design but on the ability to navigate reputational currents with tact and precision. White’s persona—his tall frame, his signature red hair and mustache, the unmistakable energy that drew eyes in any room—was itself a tool, a brand that could accelerate an exchange, convert a social connection into a patronage opportunity, and keep the firm’s doors open in times when taste was a weapon as much as an art. Yet the gloss of the era could not erase the fact that such a culture thrived on risk. The line between inspiration and exploitation was often blurred in a climate where glamour and ambition walked hand in hand. It is a difficult truth that the very networks that elevated White could, under certain lights, become spaces where rumor travels faster than fact, and where intimate lives become collateral in the court of public opinion. The drama of this section is not to condemn but to illuminate how a man like White both influenced and was shaped by a social ecosystem built on exclusivity, secrecy, and the relentless pursuit of the next big thing. In an age when the city’s face was a palimpsest of new towers and old money, White’s footprint resembles a script for a larger drama: one that asks how a single figure can push a city forward while the margins of that progress are owned by the networks that support him.

Section III: The Architecture of Total Design

White did not merely design buildings; he orchestrated entire environments, a concept contemporary readers would recognize as a radical integration of space, function, and sensation. The idea of “total design”—a holistic approach where doors, knobs, furniture, lighting, and even the social rituals surrounding a space are coordinated to create a unified experience—was not common in his time. White’s facility for this holistic craft reveals a mind that saw architecture as a theater in which people move, feel, and decide. The Trinity Church project in Boston, the early Oberlin-like sense of permanence in the Romanesque silhouettes, and later, the audacious plans for Madison Square Garden and the Metropolitan Club—each project functioned as a chapter in a larger manifesto. If architecture could shape behavior, then White could be described as a conductor rather than a mere builder, shaping atmospheres to produce the emotional effects that clients desired: awe, confidence, belonging, and, crucially, social power. The stories of his personal approach to design—how he matched interior materials to the mood of a space, how he selected lighting to alter perception, how he choreographed experiences around a building—speak to a man who understood that human behavior is as much a product of atmosphere as of intention. The “door knobs to dinner parties” line has become a shorthand for the breadth of his ambition: a single design vocabulary extended from the most intimate details of daily life to the grandest gestures of public display. The Adams Memorial, Farragut Monument, and other public works bear witness to a professional philosophy that strove for cultural resonance beyond the workshop. They demonstrate that art and public life were not separate spheres in White’s world; they were interconnected threads in a single tapestry of civic and social influence. Yet there remains a tension that lies beneath the surface of this grand narrative. The same mastery that allowed White to craft immersive environments could, in the hands of a powerful patron or a restless private mind, become a tool of control or intimidation. The tension is not a simple moral verdict but a question about the moral economy of genius: when the appetite for beauty becomes the engine of social power, what safeguards exist to protect those who seek opportunity or apprenticeship in a field that values access as much as talent? The drama of total design is not merely about aesthetics; it is about the human experience of space and the responsibilities that come with the power to shape it. White’s life, in this sense, poses a question about modernity itself: when the scale of our ambitions matches the scale of our architecture, do we produce cities that uplift all who inhabit them, or do we fracture communities under the weight of glamour and exclusivity? The artifact of his work—the spaces that continue to tell stories of privilege and taste—invites readers to reflect on what we value in the built environment and whose voices are amplified when we write history in stone.

Section IV: The Dark Current of Rumor and Power

To tell the story of Stanford White without acknowledging the whispers that have traveled through time would be to omit a vital thread of the era’s cultural imagination. The late nineteenth century was a moment when gossip could travel as fast as a telegraph, when stories about actors, patrons, and designers merged with the city’s mood and became part of the ongoing myth of the era. The charges leveled in popular media across decades—whether framed as sensational scandal or serious inquiry—reflect a broader social anxiety about the intersections of wealth, sexuality, and power. In evaluating White’s life, historians must weigh evidence with care, distinguishing clearly between documented commissions, known associations, and rumors that circulated in clubs and newspapers. The “secret apartments,” the ornate interiors, the alleged “grooming” and exploitation claims, require a careful, evidence-based approach. The ethical questions here are not merely about a single individual’s alleged behavior but about how a society that celebrated luxury and spectacle negotiates responsibility, memory, and accountability. The drama of this section lies in the tension between admiration for architectural genius and vigilance about the abuses that power can enable. It is a reminder that the story of the Gilded Age is not solely a tale of innovation and